Open-Loop ABT Costs – Tap Aggregation

In our previous article Two Fare Validation Methods in Open-Loop ABT Systems we introduced two methods of fare validation – Up-Front and Informed:

- Up-Front Validation method which uses CP (card-present) cEMV (contactless EMV) transactions.

- Informed Validation method which does not require cEMV transactions. The method comprises:

- Ride registration by means of contactless card tap (contrary to the cEMV transaction, the card tap data is not viewed by the card scheme as a transaction)

- Fare deduction from the ABT account balance (also called stored-value balance)

- ABT account balance top-up via e-commerce, CNP (card-not-present) transactions

- Positive lists of ABT credentials propagation to moveable validators

In that, previous article, we briefly asserted that Informed Validation method:

- may save on acquiring processing costs and

- is more debit card-friendly compared to Up-Front Validation method.

In this article, we will dwell on this by discussing cEMV transactions aggregation particularities.

The Cost of the Payment Transaction Processing

One of the main challengers for the Open-Loop ticketing is the cost of acquiring. For example, this article in Mobility Payments tells us a story about migration to Open-Loop ABT in the U.S. The problem is the high fixed component ($ per transaction) of credit card acquiring processing fees (also called merchant services fees). It is estimated around $0.20 – $0.25 per payment transaction, and it comprises the card schemes interchange fees and the acquirer’s margin.

The Payments community constantly applies pressure on the card schemes to reduce credit card interchange fees and cashbacks. See for example, the recent article by Dean Sheaffer, this pressure is going to work only partially.

We cannot ignore the fact that the payment transaction cost exists objectively, and it has a fixed component. Digital equipment becomes cheaper with time, but the payment transaction is not just a few bytes of data that needs to be transmitted and computed. The payment transaction is a financial artifact and it is involved in a set of business processes, including disputes, compliance, accounting, settlement, reconciliation, fraud prevention, etc.

Besides, interchange fees finance card issuing operation, including cardholder support, card materials, personalisation and mailing. This is one more reason that interchange fees will never be close to zero unless we start paying for our cards directly to the card issuers.

Before all penalties the banks pay for non-compliance are nullified by regulators, before bank and payments scheme accountants, lawyers, customer service agents, business process designers, and software developers are replaced by the artificial intelligence, payment transactions will cost something. Let’s be realistic. The payments industry cannot withstand billions of $3 ticketing transactions charging just 1.5% of the transactions value.

This brings us to the next question: how many cEMV transactions can we possibly aggregate into a single fare payment transaction?

Open-Loop Aggregation Rules Salad

While many ticketing systems are migrating from closed loop to open loop, it was discovered that the open-loop ticketing systems can aggregate less taps into a single payment transaction than the closed-loop ones. By the way, all open-Loop ticketing systems we are familiar with use Up-Front Validation method (apart from, sometimes, validation of period passes).

Note: Period passes when implemented by propagating positive lists to the moveable validators is an efficient method of increasing the aggregation level. This is an example of the Informed Validation method. This method is as well used in the closed loop solution currently provided by Payment in Motion.

What prevents open-loop ABT ticketing systems to achieve the level of aggregation the closed-loop ones have? Up-Front Validation method can only work in conjunction with card scheme rules that regulate contactless aggregated transactions processing. Let’s review the main card schemes approaches to ticketing transactions aggregating. The following subsections provide considerations for Most Aggregated Flow that is an ideal merchant flow for the Up-Front Validation method. It’s main purpose is to aggregate as many CP cEMV transactions into a single deferred CP payment transaction as the regulator allows.

Note: card schemes rules change approximately every 6-12 months. Changes in mass transit transaction aggregation frameworks are usually substantial as the industry’s experience in open-loop ticketing is relatively new.

Mastercard Cards

Mastercard Processing Rules (Hereafter “MC Rules”) of Dec 22, 2022, mention “Contactless transit aggregated transactions” around 100 times. The aggregation rules are covered in Section 4.5, with all its region/country-specific variations. Additionally, there are rules for FRR (First Ride Risk) recovery framework as well as appendixes with variations of aggregated amount limits, time period limits, and FRR limits in MC Rules.

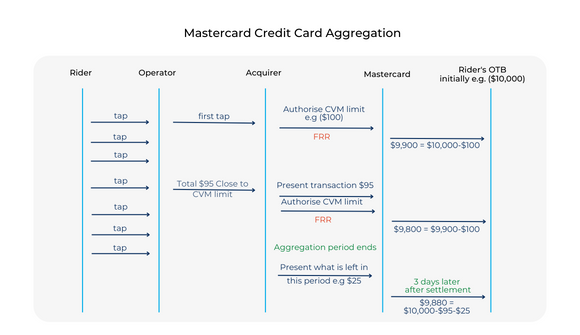

The following Most Aggregated Flow diagram is consistent with MC Rules, Section 4.5.1. We use an example there of CVM (cardholder verification method) limit for contactless transactions = $100.

The right-most vertical line in the diagram depicts the cardholder experience, in terms of their credit card account OTB (Open to Buy) balance. We assume that the card is a credit card and its OTB is substantially larger than the CVM limit (debit card cases are discussed below).

The ideal Most Aggregated Flow imposes certain logic on the transit operator. At the time of each tap, in order to aggregate as many taps as possible, the operator must be aware of each tap cost (after all discounts, concessions, caps, etc.). When the to-be aggregated total is close to the authorised value, the operator (in this ideal flow) must report the event and the amount to aggregate to the acquiring processor. If a distant/zone-based tap-on – tap-off mode is used, the transit operator must determine the potential max fare at tap-on time, and the actual fare – at the tap-off time.

In practise, transit operators deviate from the Most Aggregated Flow. For example, when the operator applies daily caps calculated in the back office after the end of day, the aggregation period may be reduced from 14 days, allowed by Mastercard, to 1 day.

Regional Variations for Mastercard Transactions

Some of MC Rules, Section 4.5.1 regional variations affect the Transit Operator’s business processes and level of aggregation. For example:

- Mexico. Aggregation period is 3 days

- USA. Aggregation period is 24 hours

- EEA, UK or Gibraltar. “A clearing message must be identified as specified by the registered switch of the Customer’s choice.”

The number of regional variations seem to be not of the transit operator’s concerns because the regulations depend on the acquiring region. The operator deals with a single set of regional variations, not all of them. For example, if the operator collects transit fares in Mexico, it is always the 3-day aggregation period, regardless of where the credit card is issued. However, we should assume that not all among several thousand card issuers in the US correctly implement Mexican transit acquiring rules. Some of them may decline transactions aggregated over more than 24-hour period. The operator in Mexico must be prepared to such noncompliance cases, and this usually takes some manual effort and costs money. Such cases may seem negligible to big transit operators. For small ones, operating near the state boarders, this may be a relevant issue.

Maestro Cards

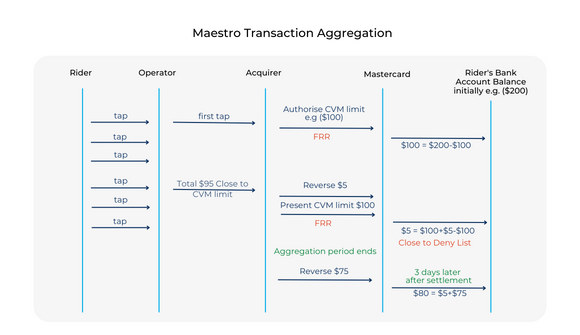

The following Most Aggregated Flow diagram is consistent with MC Rules, Section 4.5.2., which specifies Maestro card rules.

Maestro is essentially a debit card. The operator’s logic for sunny scenarios is more or less similar to the Mastercard Credit Card. Though, the rider’s experience regarding their bank account balance is different.

Usually, people don’t keep much money on their debit bank accounts, and they would like to predict how and when this money is to be spent, to be aware of the overdraft risk.

In favour of the debit cardholders, MC Rules imposes additional Maestro card rules on the transit operators.

- The aggregation period for Maestro is limited to 3 days, unlike 14 days for Mastercard. This decreases the level of transaction aggregation.

- The below rule causes additional operation costs for the transit operator:

“The Merchant must inform the Cardholder that the amount held from the available funds in the Account may be greater than the cost of a single fare, and the Merchant must inform the Cardholder of the amount of time that the Merchant requires to reverse all unused funds. This information may be provided on the Merchant’s Website, included in call center scripts, and/or displayed within the transit Merchant’s system. The Merchant must also provide specific tap. information to the Cardholder upon request.”

To comply with the above rule, the operator must train its call centre personnel on how to explain to the cardholders their specific case and provide the personnel with the actual tap and charge historical data.

Mastercard Debit Cards

Current Mastercard rules do not have specific debit and prepaid card aggregation rules, different from the credit card ones. For the time being, Up-Front Validation method for Mastercard debit and prepaid cards seems to be impractical due to high risk, poor rider experience and low level of aggregation.

In contrary, Informed Validation method can still be applied to the debit cards if CNP e-commerce transactions are allowed for the cards by the card issuer.

Visa Cards

Visa Product and Services Rules (hereafter – Visa Rules), section 5.8.7 and 5.8.18. describe and regulate Visa aggregated transactions in transit merchants. The Most Aggregated Flow, from the transit operator standpoint is similar to the one for Mastercard credit cards. Visa Electron cards do not seem to be eligible for the cEMV at all.

The considerations related to Visa Debit cards are similar to the ones for Mastercard Debit cards. Only Informed Validation method seems to be practical for them.

Some Regional Debit Cards

Australian Eftpos

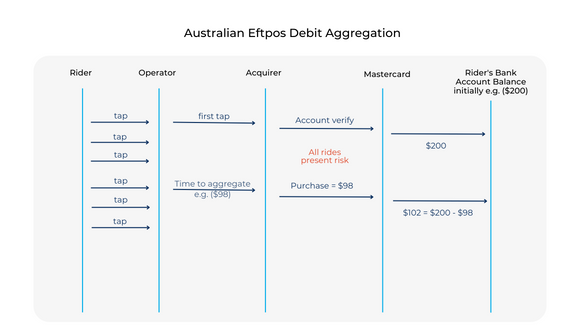

According to eftpos Technical, Operations and Security Rules (hereafter – Eftpos Rules), the transit operator is limited in the aggregated transaction amount (Australian $100) but is not limited in the aggregation period. The latter is the operator’s risk.

When the transit operator decides to aggregate, it posts the purchase transaction. If this transaction is declined by the issuer (for example because of low cardholder’s account balance, the operator may retry the purchase transaction later, up to 8 times. The operator must support the Deny List of cards failed Verify or Purchase transactions.

Note: eftpos does not seem to be used for transit ticketing in Australia yet.

The Most Aggregated Flow pertinent to Eftpos Rules is presented below.

Debit Card in the U.S.A.

Unlike Eftpos in Australia, Interac in Canada, or Maestro in Europe, a single country-wide debit card scheme, does not exist in the US. Visa and Mastercard debit cards are predominant there. Only these cards support cEMV. Transactions related to these cards may be processes via Visa/Mastercard networks (generally, as dual message transactions), or via the regional debit networks (e.g. NYCE, Shazam, Star, etc. – generally as single message transactions).

Note: processing transaction via dual message system presents an additional risk of overdraft for the debit cardholders. The above Maestro flow demonstrates the single-message framework, where the cardholder’s bank account is debited/credited immediately at the time of purchase/reversal transaction. Applying dual message system would confuse the debit cardholder even more. The dates of posting aggregated transactions to the cardholder’s bank account may be 1-3 days after the transaction authorization date.

The fixed interchange fee component for Visa and Mastercard debit cards is 25%-40% lower than for the credit cards. Thus, like the credit cards, we need to aggregate debit card taps to reduce the processing fees.

Canadian Interac Debit Card Scheme

Interac attracts some transit ticketing vendors because of low Interac processing fees. (See, for example Mobility Payments comparison table here). Some pilots have already started accepting Interac taps in Canada. There are, however, certain concerns that should be taken into consideration:

- Current Interac contactless applications in various form factors (cards, Google Wallet Apple Pay) in the field do not seem to be fully EMV-compliant. Specifically, they might not support Offline Data Authentication. If Interac does support ODA, its proprietary algorithm is not publicly disclosed.

- If Interac is going to create a new, cEMV application to resolve ODA issue, Interac cards need to be reissued. Before this, both Up-Front and Informed Validation methods may be fraud prone.

- Many issuing banks surcharge Interac cardholders for debit transactions or offer costly fees for unlimited debit transactions option. This makes Up-Front validation method not practical unless the aggregation level is high.

- Note: the banks may amend this approach, at least for now, during several open-loop pilots in Canada (see for example this article). How such policies can be sustainable – remains to be seen.

- Interac rules for transit transactions aggregations are not publicly disclosed, and we cannot tell how they are aggregation-friendly, merchant-friendly, and cardholder-friendly.

Note: We asked Interac Corp for comments, and we will publish them as soon as we receive them and discuss them with Interac Corp.

First Ride Risk Cost

The transit operators consider First Ride Risk (FRR) low because nobody orders cards or opens bank accounts with intention to get a free ride once. Usually, free ride occurs because of a genuine cardholder mistake. Most operators have high rate of first ride fare recovery.

Let’s ask a different question: how much does it cost for a transit operator to recover the first ride fare? Payment transactions cost money. Different card schemes propose different recovery frameworks. For example, Eftpos Rules allow to try up to 8 times to debit the cardholder’s bank account.

Besides, business processes for transactions recovery need to be specifically designed and maintained. For example, the operator needs to include the failed card in the deny (hot, stop) list, and exclude the card from that list after successful recovery. It may be even impractical to seek recovery for most of free rides, especially the cheap ones.

For comparison, Informed Validation method bears FRR only if wireless connectivity with moveable validators is constantly poor within several minutes before the card tap.

Takeaways

- Informed Validation method provides lower acquiring processing fees because of better transaction aggregation.

- Up-front Validation method requires aggregation of CP cEMV transactions.

- Card schemes rules change often, and they have many regional variations.

- The transaction aggregation costs time and money to the operator because their business processes need to be re-designed and operation expenses will rise. Such expenses may be unsustainable for small- and mid-scale transit operators.

- Lower level of transaction aggregation causes unsustainably high acquiring fees.

- Aggregation of CP cEMV transactions may be impractical for debit cardholders due to the poor rider experience.

- The Informed Validation method has its own costs of implementation as it requires reliable cellular coverage for moveable validators. We do not suggest that all ABT open-loop ticketing systems should switch to this method. We only suggest that this kind of decision is to be made or not made after thorough considerations of all factors, and we provided such factors and considerations in this series of our articles. In many cases, both validation methods can be applied in parallel.

Credits

- We are grateful to LIttlepay and Masabi for their remarks and contribution to this section.

- Many thanks to Dean Sheaffer for his insights on the interchange fees context in the US.

- We thank Juan Liverant, CEO, Payment In Motion for his feedback and contribution with the Canadian context.

Authors: David Lunt, Technical Director, Melbourne & Eugene Lishak, Associate, Toronto, Payments Consulting Network

David and Eugene have worked on ticketing systems since 2011 and 2008 respectively. They both bring a wealth of knowledge to the Payments Consulting Network on this topic.

***

This is part of a series of transit articles.

If you found this article helpful and would be interested in reading similar articles by our consulting team, please subscribe to our newsletter.

To get notified of our latest posts, follow Payments Consulting Network company LinkedIn page and click on the bell icon at the top right section of our company profile.