The Shift to Electronic Payments – Some Policy Issues

The Australian payments landscape is continuing to evolve rapidly. At the RBA, we have a broad mandate to promote efficiency, competition and safety in the payments system. Today, I will focus on the remarkable shift that Australians have made to paying for goods and services electronically, particularly using cards. This shift has delivered significant benefits to businesses and consumers. It also raises some important payments policy issues and I’ll outline the approach that the RBA is taking to address them.

Cards are now the main way Australians pay

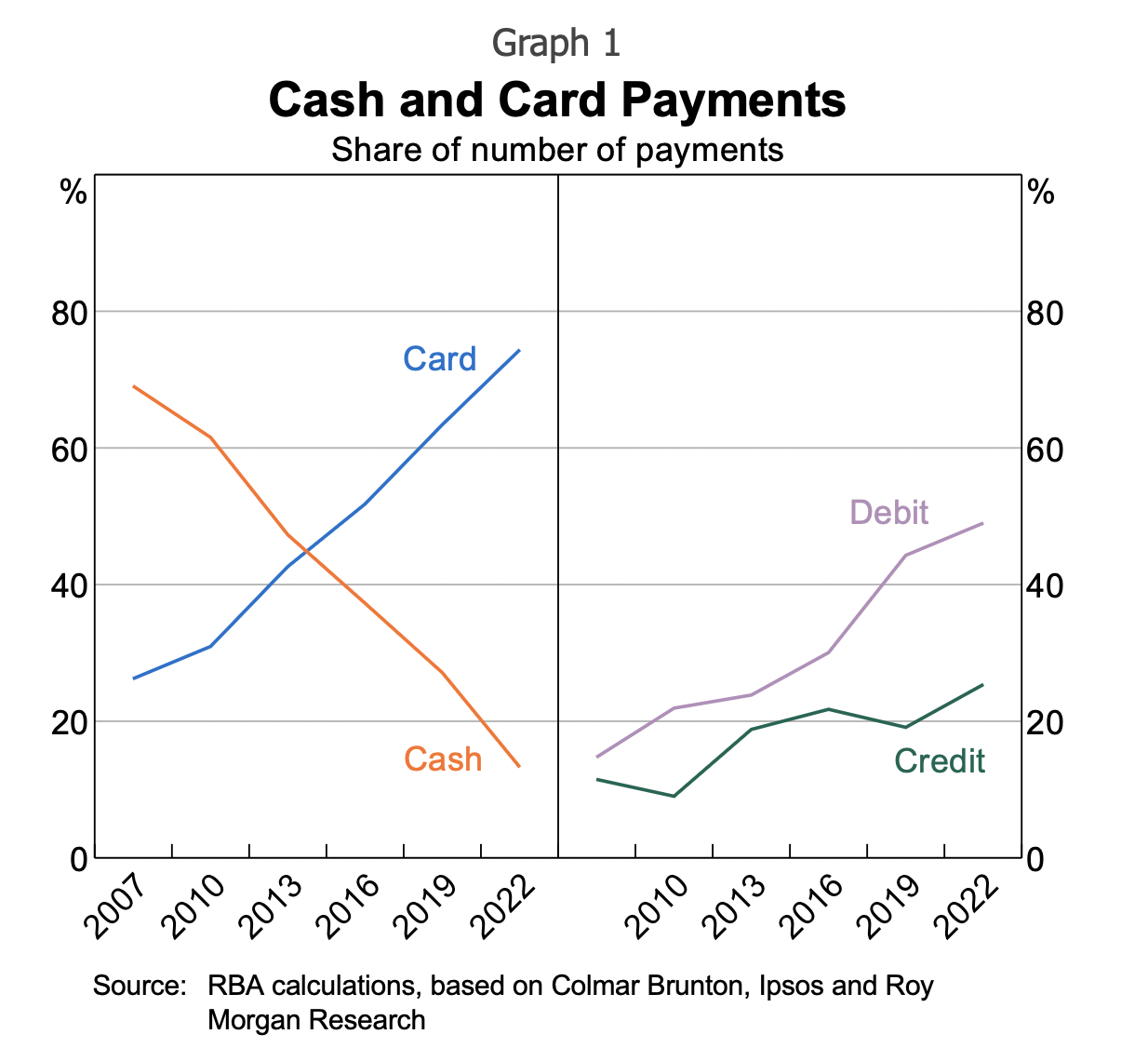

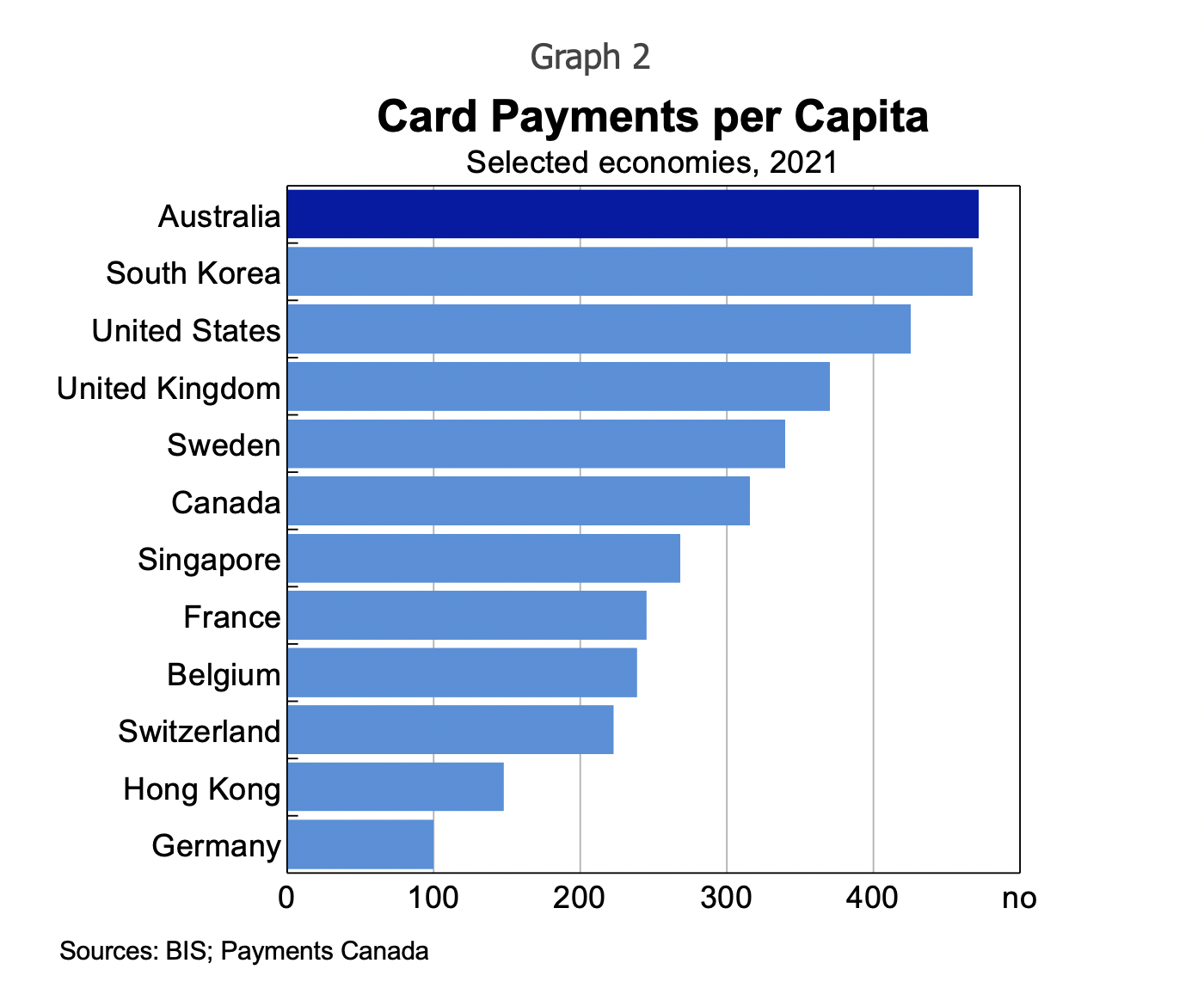

Over the past fifteen years, there has been a striking shift from paying by cash to cards. In the Consumer Payments Survey we conducted late last year, only 13 per cent of transactions were made using cash; this share has halved over the past three years (Graph 1).[1] Instead, consumers are making three-quarters of their payments using the card networks – half with debit cards and a quarter with credit cards. Australians make card payments more frequently than in many comparable economies, including those with very low rates of cash usage, such as Sweden (Graph 2). In some economies, merchants and consumers are now using fast account-to-account payment systems as an electronic alternative to cards, and I will return to this later.

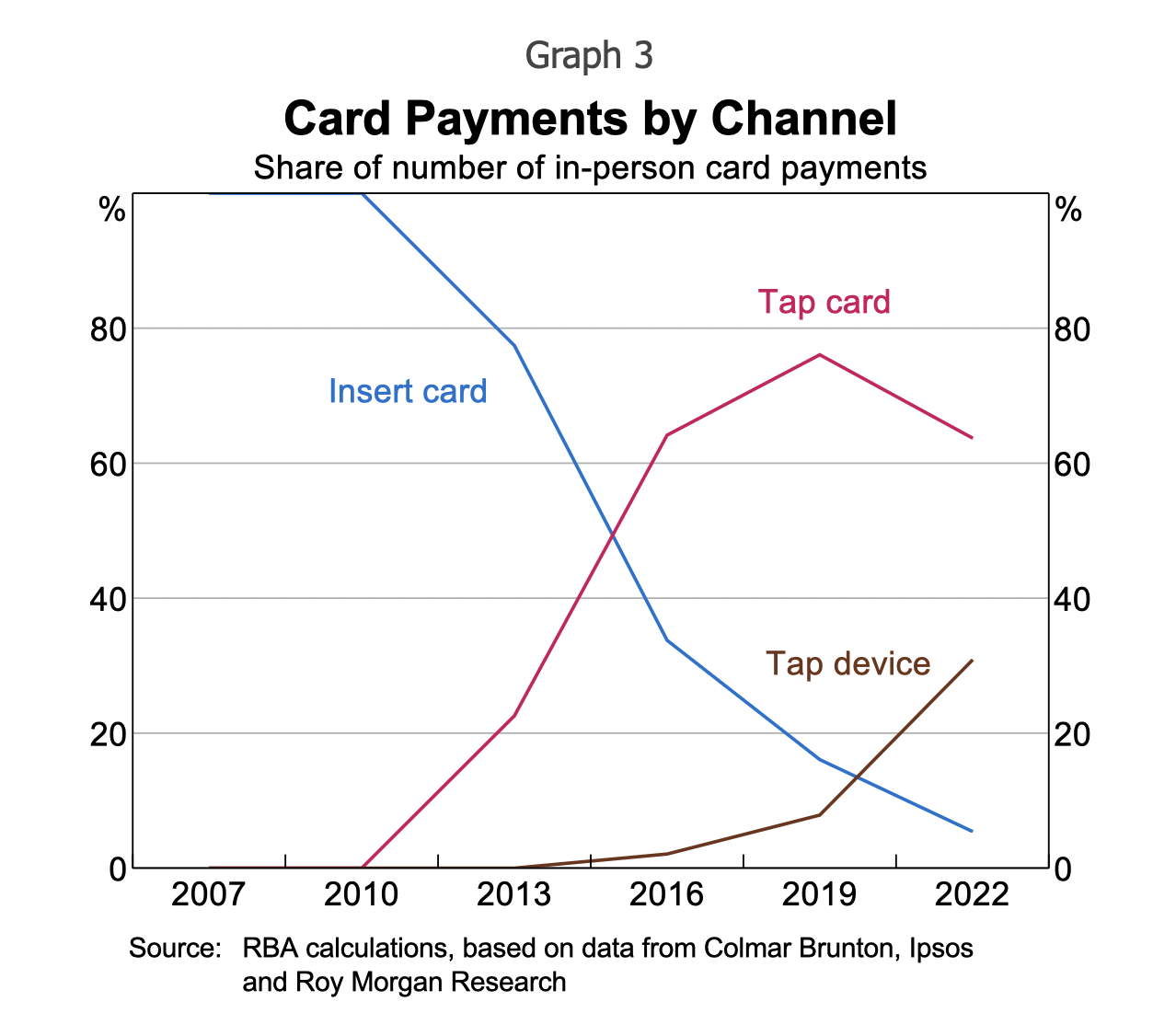

Card payments technology has become much more convenient for consumers to use. Fifteen years ago, almost all in-person card transactions were made by inserting the card into a terminal and providing a signature or PIN for verification. These days, transactions mainly just involve tapping a card or a mobile device that securely stores card details (Graph 3). In addition, with the growth of e-commerce, consumers are making around 15 per cent of their card payments online.

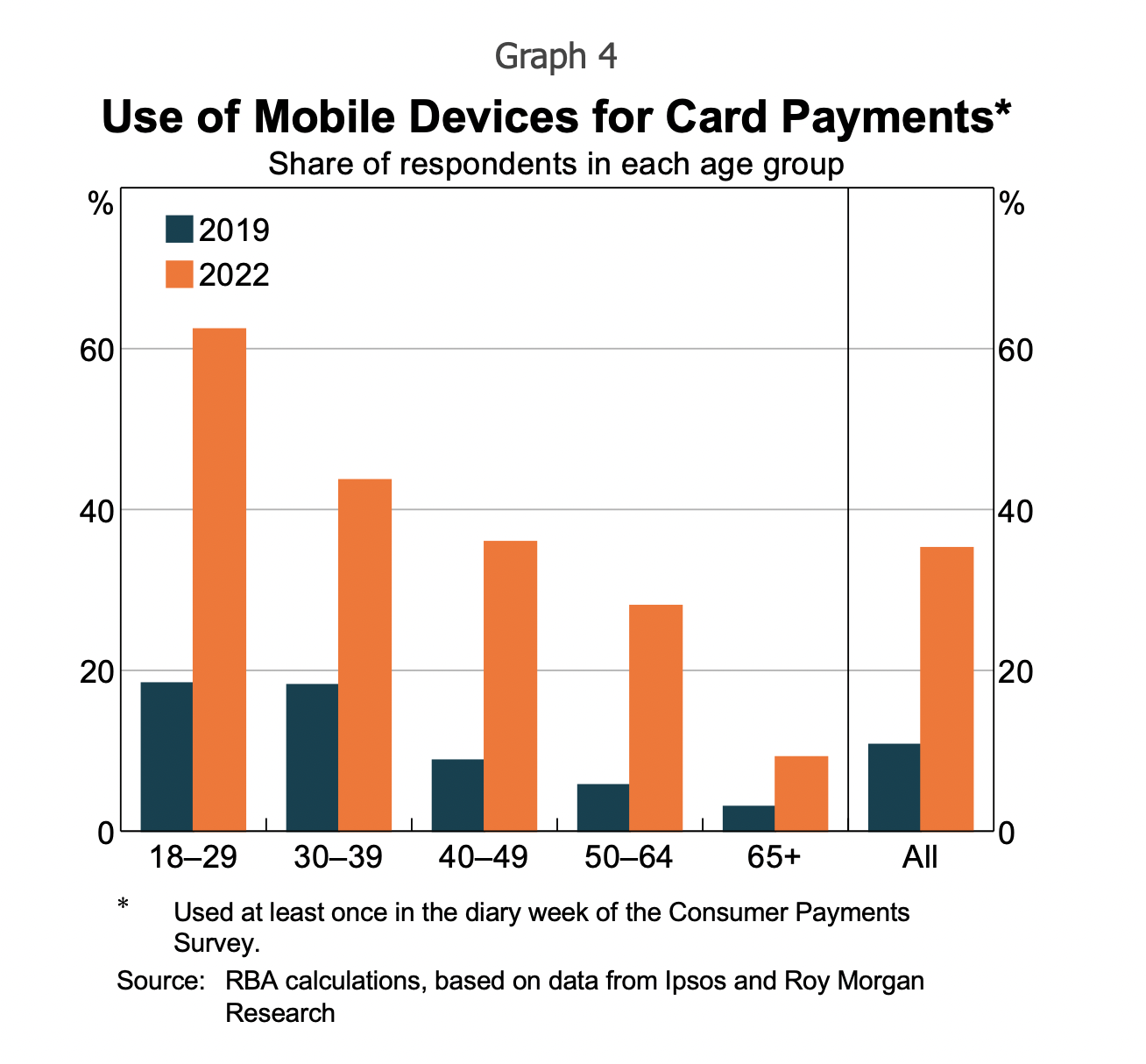

Use of mobile devices for card payments has grown rapidly over recent years. Around a third of consumers made a contactless payment by tapping a mobile device in the latest Consumer Payments Survey. Adoption increased substantially across all age groups over the past three years, particularly for younger consumers (Graph 4).

The dominance of cards and the consumer shift to mobile devices raise some important issues within the RBA’s mandate. We are focusing our efforts on:

- lowering card payment costs for merchants

- supporting the development of alternative payment methods, such as the New Payments Platform (NPP), Australia’s fast payments system

- enhancing the safety and resilience of retail payment systems.

Lowering card payment costs for merchants

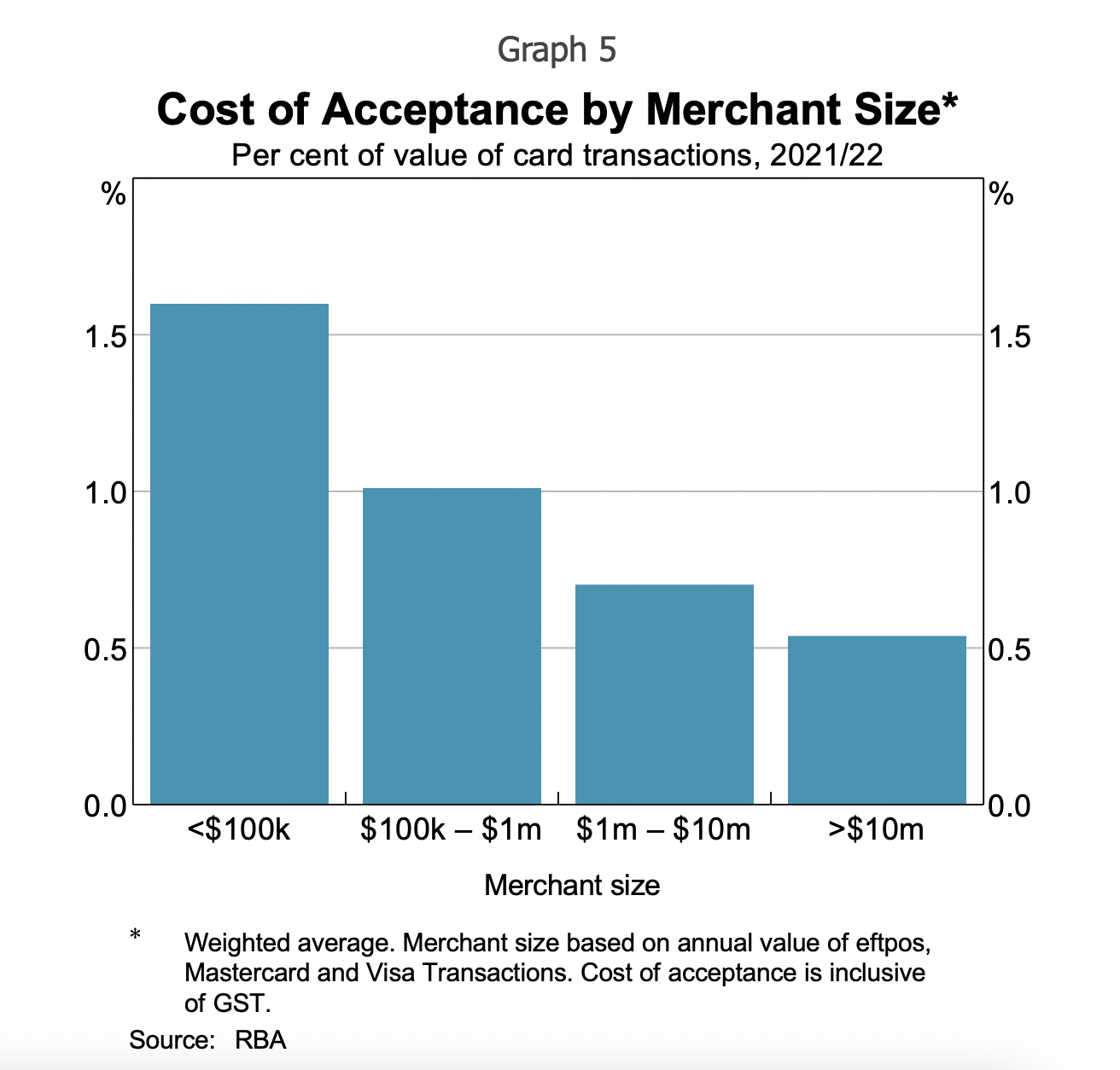

The RBA has a longstanding focus on lowering card payment costs for merchants. Our regulation of interchange fees has directly lowered costs. In addition, merchants having the choice to recover their payment costs through surcharging has put competitive pressure on the card networks and payments service providers to lower their fees. Nevertheless, the cost of card payments can still be substantial for small businesses (Graph 5).

The trends in card payments I highlighted earlier are putting upward pressure on merchant payment costs. This has been most evident in debit card use. In the past, customers inserted their debit card into a terminal at the point of sale and selected ‘cheque/savings’ for it to be routed through the eftpos network or ‘credit’ for it to be routed via the international networks (Mastercard or Visa). It turns out that most people selected ‘cheque/savings’. The shift to tapping cards and mobile devices, however, has resulted in most debit card transactions being routed to Mastercard and Visa and away from eftpos. With the international networks on average costing around 20 basis points more to accept for in-person transactions, this has resulted in an increase in merchant costs for accepting debit card payments. In addition, the shift to online commerce has contributed to higher payment costs. It costs more to safely process online transactions, but there has also been less competition between the card networks, particularly prior to eftpos entering this market over the past year or so.

We have also observed that higher wholesale payment costs are charged for small businesses, and for mobile wallet and online transactions. These wholesale payment costs include: interchange fees, which are paid by acquirers to card issuers; and scheme fees, which are paid by acquirers to the card networks.[2] All these costs are then passed on by the acquirers to merchants. Although these costs are typically not visible to consumers, they ultimately pay for them through higher prices for goods and services.

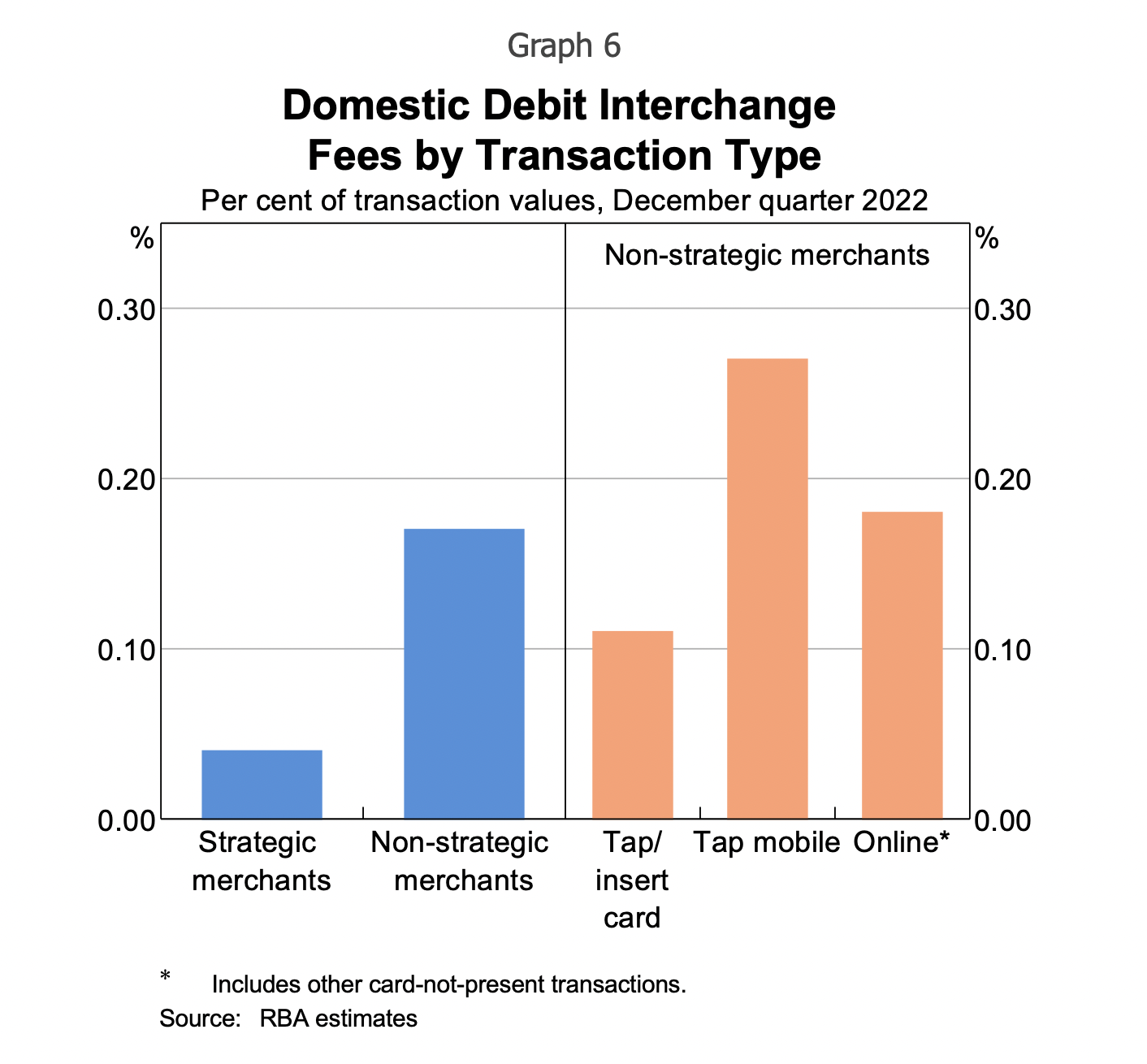

- Interchange fees are much higher for small businesses. Very large businesses negotiate low ‘strategic’ interchange fees across all their card transactions. In contrast, the interchange fees for small business transactions tend to be much higher and we have noticed that they often face even higher rates for mobile and online transactions than when a card is tapped (Graph 6).[3]

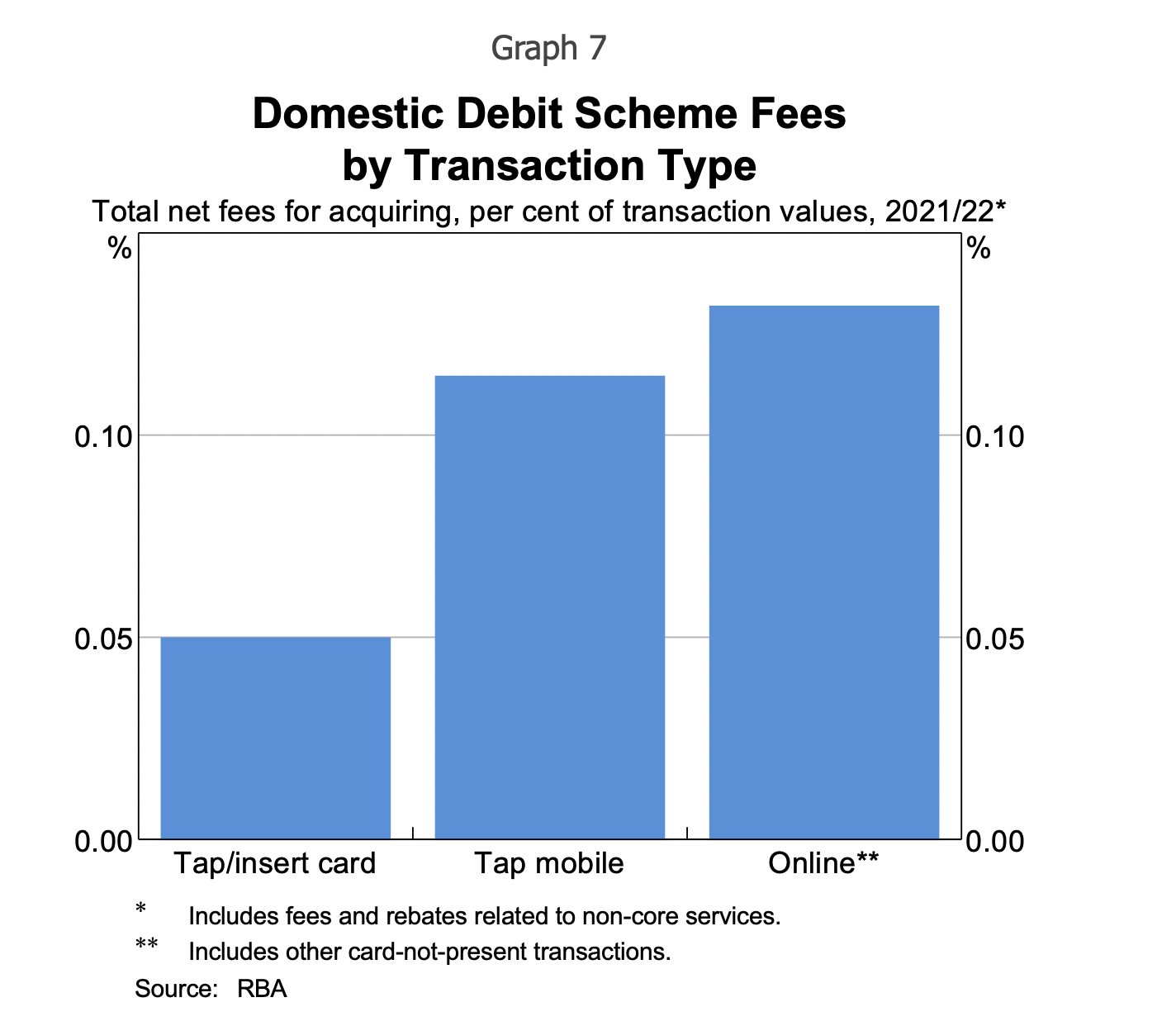

- Scheme fees are higher for mobile and online transactions. While scheme fees don’t seem to vary by the size of the merchant the way interchange fees do, higher scheme fees are charged on mobile and online transactions than when a card is tapped (Graph 7). There may be some good reasons for the card networks to charge higher fees for some types of transactions, such as to cover the cost of making online transactions more secure. At the same time, it is possible that these fees could be lower if there was more competition in payments, particularly for mobile and online transactions. I’ll provide more details in a few moments on what we are doing to promote competition by improving the transparency of scheme fees.

Reducing debit card payment costs for merchants through least-cost routing

The RBA is focused on increasing competition in the debit card market to keep downward pressure on payment costs for merchants. The main priority here is to allow merchants to choose the lowest-cost card network (eftpos, Mastercard or Visa) to process their debit transactions; this is known as ‘least-cost routing’ (LCR). As I mentioned earlier, the international networks on average cost around 20 basis points more to accept than eftpos for in-person transactions. For merchants to take advantage of LCR, payment service providers need to upgrade their systems to support it for transactions made by tapping a card or a mobile device, or online.

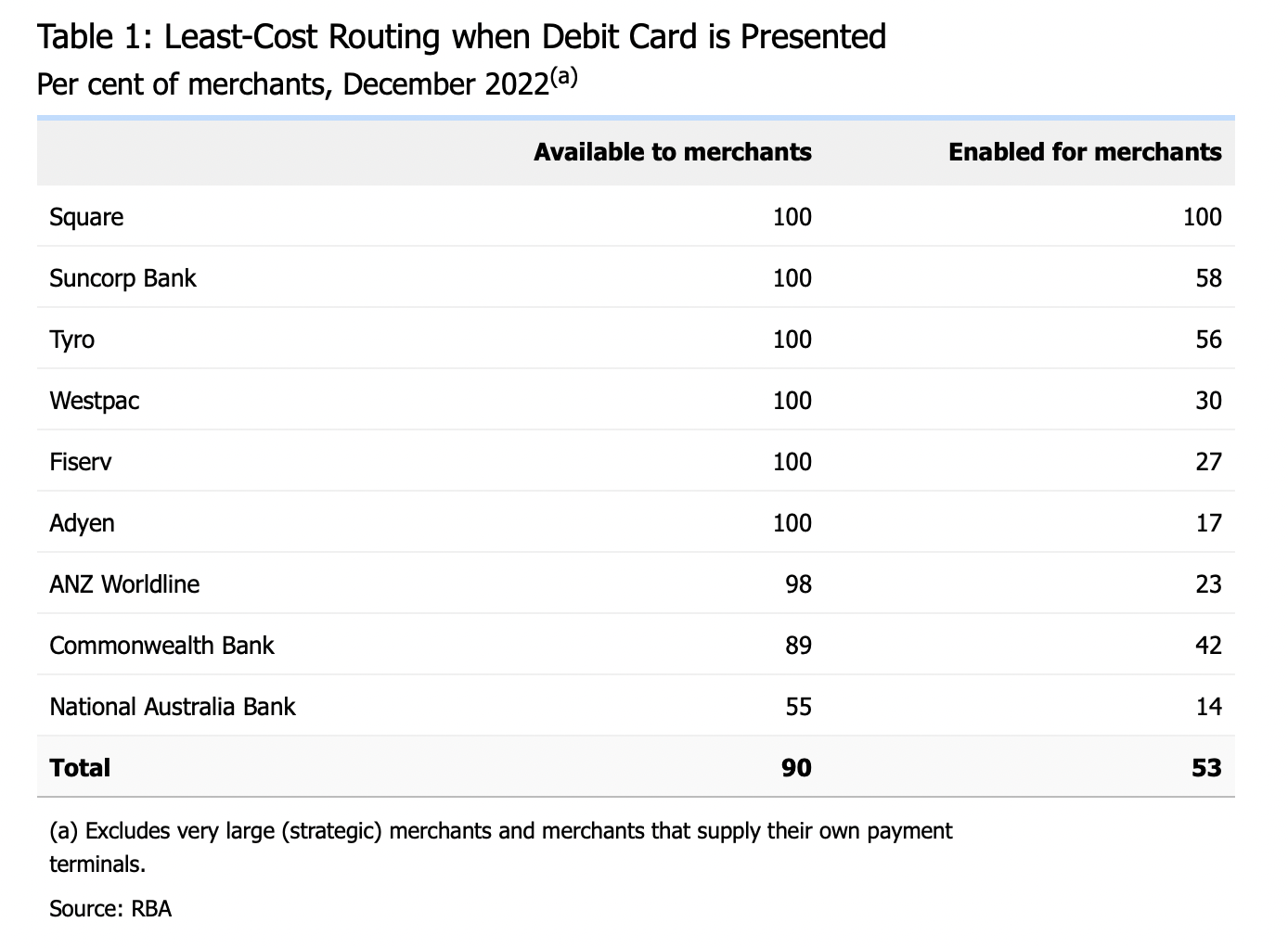

To provide greater transparency on whether providers are supporting LCR, today we are publishing for the first time a report on LCR availability and take-up across the major acquirers (Table 1).[4]

This first report covers transactions where a card is tapped. Providers have generally made good progress, with LCR available to be turned on for 90 per cent of their merchants. Where there are gaps in availability, this is mainly due to providers needing to upgrade old terminals. These providers have assured us that this will be completed over the next year. We will publish an updated report every six months, which will ensure that these providers are held publicly accountable for delivering on their commitments.

In contrast, the take-up of LCR by merchants remains disappointingly low, with just over half of merchants on plans with LCR enabled. Merchant groups have consistently highlighted that LCR is not easily accessible for merchants in practice. The report highlights that some providers have been much more successful than others in moving their merchants across to plans with LCR. Providers that have yet to enable LCR for all their merchants should proactively encourage them to take it up, since it makes our payments system more competitive and puts downward pressure on merchants’ payment costs.

For online transactions, the RBA set an expectation that providers would be offering LCR to merchants by the end of last year. We recently received the first round of reporting from providers. While a lot of work is underway, the industry has not met this timeline, which is disappointing. We expect to see substantial progress by June this year on enabling LCR for merchants online. In the interest of transparency, we intend to include a table on LCR for online transactions in the next report, so merchants can know which providers are actively supporting lower payment costs.

The final frontier for LCR is mobile wallet transactions through Apple Pay, Google Pay and Samsung Pay. This is particularly important given the rapid growth in the use of mobile devices for in-person card transactions. We have been engaging regularly with the mobile wallet providers over the past year and have concluded that it should be feasible to introduce LCR for mobile wallet transactions by the end of 2024. The mobile wallet providers and other industry participants are working towards meeting this timeline.

Improving transparency of scheme fees and mobile wallet transaction fees

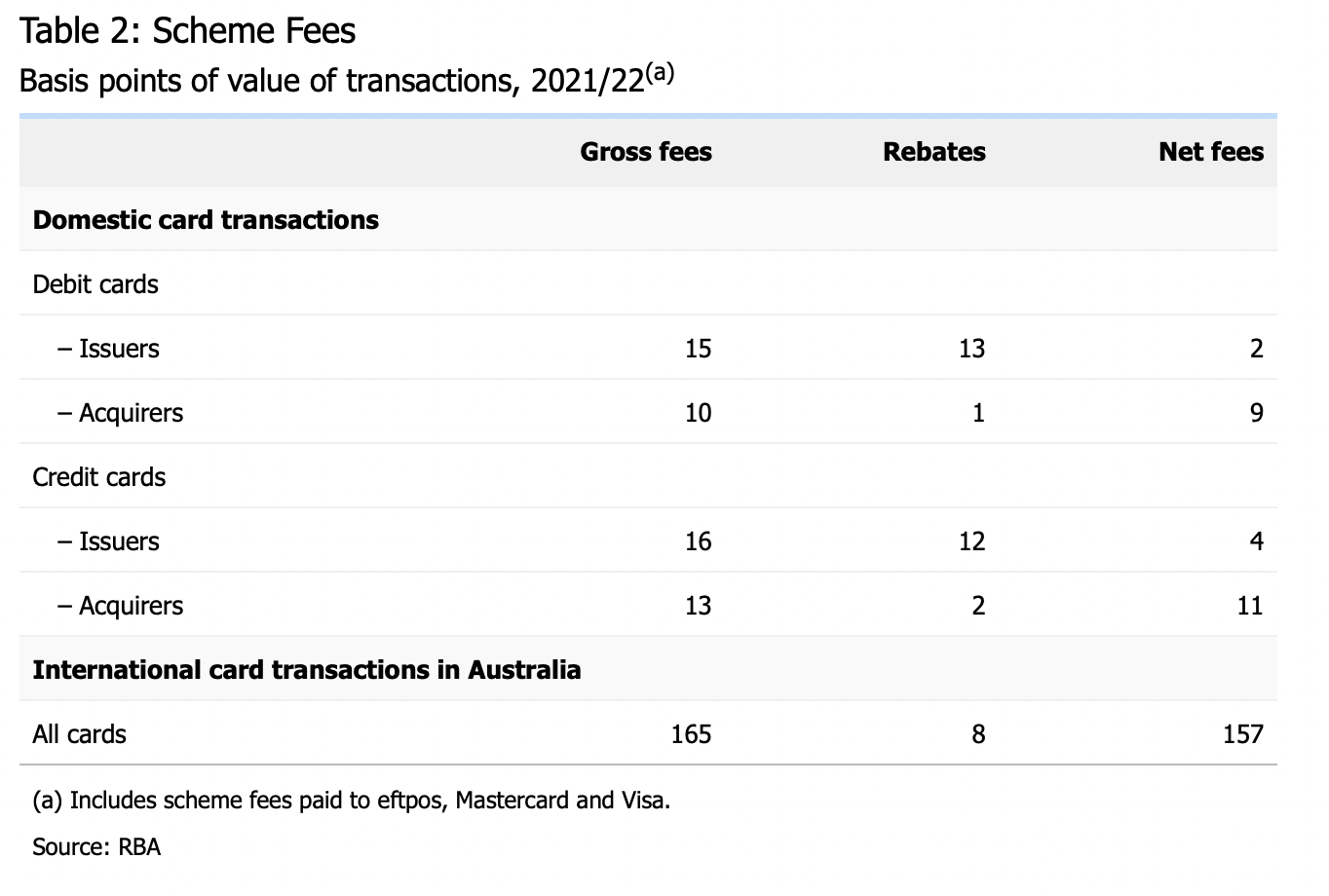

Another initiative we are pursuing is to improve the transparency of scheme fees. These fees are payable by both acquirers and issuers to the card networks for the services they provide. These fees tend to be complex and opaque. We have also heard reports that the number and level of schemes fees has been drifting up over time. To help address these concerns, the RBA has started collecting annual data on scheme fees to improve transparency (Table 2).

Scheme fees make a significant contribution to payment costs, with net fees of around $1.2 billion being paid by Australian issuers and acquirers to the card networks in 2021/22. On average, the card networks charged issuers 15 basis points and acquirers 10 basis points of the value of the domestic debit card transactions they processed. However, the networks also provide rebates that are significantly larger for issuers than acquirers. Once we take these into account, the net scheme fees paid were 2 basis points for issuers and 9 basis points for acquirers; this cost for acquirers then gets passed on to merchants. The scheme fees for domestic credit card transactions were a little higher than for debit cards. However, scheme fees were much higher for international transactions, which helps to explain why they are so expensive for consumers and merchants.[5] Beneath these aggregates, there is a lot of variation in scheme fees between the different card networks. By publishing these data each year, we hope to generate more competitive tension in the market. We will be keeping a close eye on the trends in scheme fees over time.

Greater transparency could also help to boost efficiency and competition for payments using mobile wallets. The mobile wallet providers require card issuers to enter into confidential agreements so that their customers can use these wallets to make card payments. As a result, there is very little information in the public domain about how much issuers have to pay the mobile wallet providers for this service. However, there are media reports that the cost could be over $100 million per year and would be growing quickly as more consumers use mobile wallets for payments. Given these developments, we would support steps to promote transparency of the payment costs associated with using mobile wallets.

There is currently some uncertainty about the extent to which the RBA’s regulatory powers apply to new players in the payments system, such as mobile wallet providers. To address this, we are assisting the Australian Government with its plan to reform the regulatory architecture for payments. This will include modernising the Payment Systems (Regulation) Act 1998 with updated definitions of a payment system and its participants. Our preference will remain to engage with industry in a spirit of cooperation to address payments policy issues. These reforms will enable the RBA to credibly deal with a wider range of issues associated with new payments technologies and business models.

Supporting the development of Australia’s fast payments system as an alternative payment method

While cards are currently dominant in Australia, when we look to other countries in our region, we can see alternative models of electronic retail payments that are less reliant on cards. In Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand, merchants are providing QR codes that their customers can use to pay them by account transfer through fast payment systems. These merchants and consumers have a fast and low-cost electronic alternative to card payments.

We could see a similar wave of retail payments innovation unleashed in Australia through the NPP and its PayTo service. This service provides a convenient and secure way for consumers to authorise merchants to initiate a payment from their account via the NPP. PayTo will modernise the way we make direct debits by giving customers more control. It can also be used by merchants as an alternative to cards for online and instore purchases, using QR codes to make the process convenient for consumers. There are many fintechs developing innovative retail payment services that leverage PayTo. While the service was formally launched in July last year, only one of the major banks met the industry-agreed timeline to make the service available to its customers. It is difficult to promote PayTo to merchants without a strong network of banks offering it. The other three major banks have committed to connecting their retail customers by the end of April and they have indicated that they are on track to meet this timeline. This should deliver the critical mass of consumer accounts for payment services to launch using PayTo.

Enhancing the safety and resilience of retail payment systems

Australians are relying on electronic payments more than ever, so our retail payment systems must be safe and resilient. Historically, the RBA has supervised the safety of payment systems that handle high-value payments for key financial market infrastructures, given their potential to propagate stress through the financial system. This supervision has focused on the Reserve Bank Information and Transfer Service (RITS), Australia’s real-time gross settlement system. The RBA will now extend this supervision to include payment systems where an outage could cause significant economic disruption and damage confidence in the financial system. This will include the retail payment systems that the Government has declared to be critical infrastructure: Mastercard, Visa, eftpos and the NPP. We will draw upon the relevant international standard – the Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures – focusing on the payment system operators’ risk management frameworks, particularly regarding operational risk. We will also integrate the operators’ obligations under the Government’s critical infrastructure regulations. The RBA is consulting with industry on the updated framework and is engaging closely with other regulators to ensure that the regulatory burden on the industry is minimised.

A key focus will be on the safety and resilience of the NPP. The NPP processes payments 24/7 in real time and Australians expect the system to be available when they need to use it. This is particularly important given industry discussions on potentially retiring the Bulk Electronic Clearing System (BECS), which currently processes most account transfers, including direct debits and payroll. If BECS were to be closed, the NPP would become the main payment system for retail account transfers. For the NPP to be an effective replacement for BECS, the industry also needs to make sure accounts that send or receive payments are reachable. To monitor progress, the RBA will require financial institutions to report to us on their work to connect all relevant accounts to the NPP. All Australians should be able to access payments services using this important national infrastructure.

Conclusion

We have seen rapid change in the retail payments landscape over the past fifteen years. Cards have become the dominant retail payment method and consumers find them very convenient to use. At the same time, there are some policy issues raised by card payments that need to be addressed. We look forward to working with the industry to address these issues as we promote an efficient, competitive and safe payments system.

Author: Ellis Connolly, Head of Payments Policy, Reserve Bank of Australia.

***

This is a transcript of the full speech delivered at the AFR Banking Summit on 28 March 2023, which has been republished with permission from the Reserve Bank of Australia.

***

[*] I would like to thank Cameron Dark, Boston Dobie, Troy Gill, Annalisa Heger, Qiang Liu, Thuong Nguyen, Grant Turner, David Wang, Ben Watson and Tim West for their excellent assistance in preparing this speech.

[1] The RBA has conducted the Consumer Payments Survey every three years since 2007, with the latest survey conducted late last year. The survey is a representative sample of around 1,000 Australians. Participants are asked to complete a seven-day payments diary recording all payments they make during the week, and a post-dairy survey that asks qualitative questions about payment preferences. More results will be released mid-year in a planned Bulletin article and Research Discussion Paper.

[2] Acquirers provide merchants with facilities and services to accept card payments. Issuers provide customers with cards and process payments for them.

[3] The differences in interchange fees partly reflect differences in transaction size, with transactions involving tapping a mobile on average smaller than those involving tapping or inserting a card. However, even in terms of cents per transaction, mobile and online transactions are costlier: the average interchange fee per transaction is around 6 cents for tap/insert card, 9 cents for tap mobile, and 15 cents for online.

[4] The report on LCR availability and take-up is available on the RBA website: <https://www.rba.gov.au/payments-and-infrastructure/debit-cards/least-cost-routing.html> and <https://www.rba.gov.au/payments-and-infrastructure/debit-cards/least-cost-routing/update-on-implementation.html>

[5] Interchange fees for international transactions are also very high, and the RBA has required card networks to publish these interchange fees on their websites.